I’ve come to know Ed Moses as a result of a friendship with his son, artist Andy Moses. In the last few years Ed became my client and a friend who, at the age of 89, continues to work early each morning on his art. It’s been inspiring to witness an artist who continues to create fresh and innovative artwork after seven decades. Ed is one of the original group of Venice artists known as the “Cool School,” who were essential to the creation of contemporary art in Los Angeles as it exploded onto the world stage in the ’60s and ’70s. He experimented with a vast array of techniques and media, but he remains above all perhaps the most influential Abstract Expressionist of postwar Los Angeles. This interview took place in March at Ed’s Venice studio in conjunction with a retrospective of his drawings currently on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and solo exhibition at William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica.

Stephen Goldberg: What I notice in the LACMA catalog of your show is that the first drawings you did appear to be biomorphic. Were those drawings influenced by Willem de Kooning or Arshile Gorky, because at least one is dated 1958?

Ed Moses: Yeah, they were very much influenced by de Kooning, and somewhat by Gorky.

Okay. So how did you manipulate it?

Well, the shapes used by de Kooning or any of the people I was influenced by at that time, I fed off those shapes in exaggerated ways and played with the images coming up with my own extrapolations of those drawings.

Did you see de Kooning’s works in person somewhere?

I went to New York in ’58 so… yes, I think I could have seen the de Kooning drawings. I was in a 10th Street co-op called Area Gallery, and I had a show at Barone Gallery.

At Barone were they drawings or paintings?

They were abstract paintings influenced by Milton Resnick and Willem de Kooning. I loved the shapings that they did and I made these paintings with a stick dipped in enamel paint to make abstracted feminine forms. And then over the stick paintings I had a large palette that I’d scraped up wads of white paint and sculpted across, filling in forms and shapes… I looked up Resnick when I first arrived in New York. I managed to find a studio which was an old dental office that was 10 x 10 feet-wide and I shared a bathroom with four other artists. Because of the 10th Street gallery, Barone invited me to her show at her gallery uptown, where I got a great review from Dore Ashton.

I understand you knew some of the Abstract Expressionist artists from the Cedar Tavern.

Everybody hung out at the Cedar. I met Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, Franz Kline, who took me and John Chamberlain to a jazz place where Thelonious Monk was playing.

Were you influenced at all by Guston’s work?

Yes, I love Philip Guston. I’m sure I was influenced with this idea of locating a center and moving out to the sides all the way around. The center was setting up an aura of brushstrokes around it, moving out from it in all directions.

Did you discuss that with him?

I had the good fortune of talking with Guston in LA as well as in New York at the Cedar bar. Franz Kline had a table that we all hung out at.

It seems as if your entire career was influenced by these AbEx artists.

Also the Ferus Gallery in LA. Craig Kauffman and I were fellow students at UCLA and he was by far the most sophisticated of the artists that were at the Ferus Gallery and I was introduced by Craig to Walter Hopps, [one of the owners], and eventually I had a show there. Although even within that group of painters, I isolated myself into these graphite drawings they are showing at LACMA.

And why did you do that, because the other Venice artists were more into Hard Edge painting better known as Finish Fetish, and they were your friends—but you deviated away from that into these drawings?

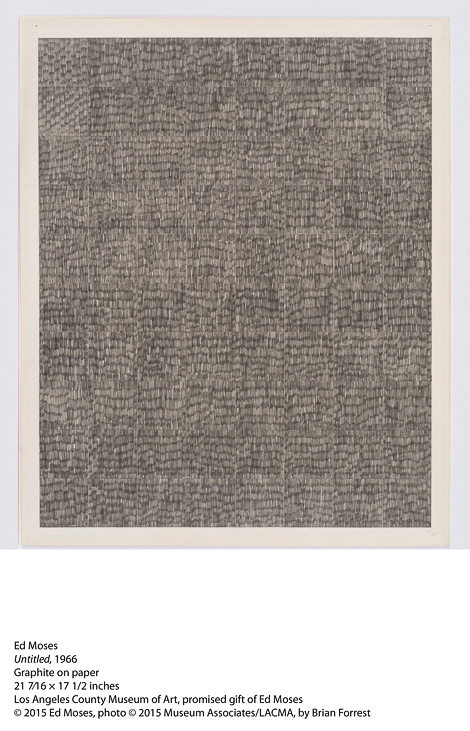

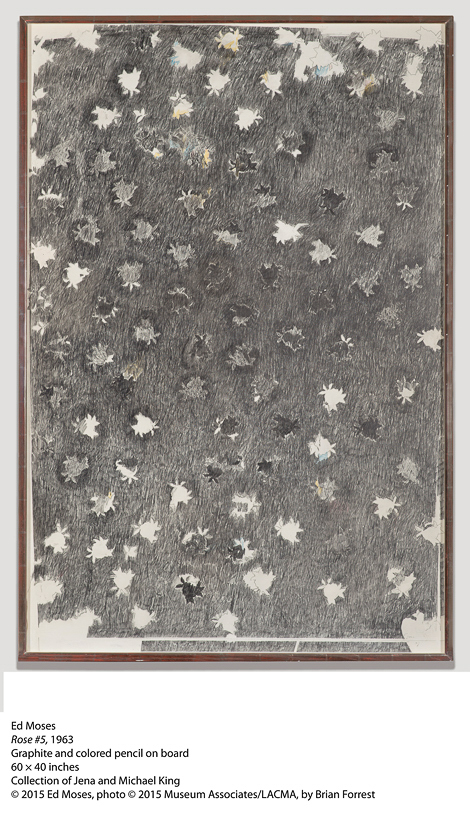

Yeah, I got sidetracked in these graphite drawings that were repetitive compulsive markings that expanded to the edges of the paper or board. The earliest rose drawings came from a piece of oil cloth that I found in Tijuana, where I traced and isolated roses on the oil cloth and transferred those to the Strathmore board by using carbon paper. I drew in the rose pattern with the graphite pencil. I’d never had any interest in being an artist as a young man but I took drafting in high school and I was very much into making lines and abbreviating dimensions.

And this training…

Sensitized me to the quality of dimensional lines. It could be very hard and very soft depending on the graphite if it was a 4H, which was a very hard defined line, to a HB, which was a very soft line. I started making repetitious strokes filling in the areas that I described with the yellow carbon paper so the outside of the line describing the flower had a yellow halo and then I filled in the shape of the rose by compulsive markings setting up a kind of density by the pressure of the graphite. I thought the density might imply a kind of magical presence.

But they were still representational?

They were in the sense that they were flowers but they looked more like shapes.

And they were used on the decorative screen that’s in LACMA’s permanent collection and is in the show.

Yes.

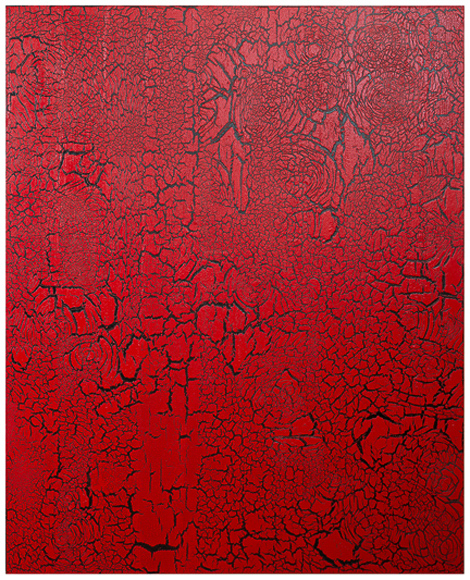

It seems that the rose image also appears in the so-called crackle paintings that you did in 2012. Was that intentional?

That was just accidental. I chipped through the craquelure and it materialized into shapes that repeated across the canvas. When I discovered the craquelure process, I wanted that kind of a surface, a cracking on the shapes and what I did is I punched the canvas after I found this material that I call secret sauce that I had applied to the surface.

In the ’60s it seems like your work consisted more of drawings than paintings?

Yes, I got obsessed by graphite drawings. They emerged out of Swedish greeting cards—when you opened them up they became three-dimensional. I abstracted the floral designs and made cutouts so when you had these three dimensional surfaces. I also based them on a building across the street from my studio in Venice where I joined Bob Irwin and Billy Al Bengston. Irwin moved out first, then I took over his place which was on the first floor and expanded from Pacific all the way around the corner.

That was from around ’66?

Right.

There are one or two of these 3D pieces in the LACMA show. It doesn’t seem like you returned to 3D cutouts much, if at all?

No.

So it was more of a kind of experiment?

Obsession. I engaged the idea of obsessive compulsiveness in applying graphite and being involved with the density of the graphite. If I pressed hard enough, I would press to manifest some magic. I never quite did the magic.

What were you trying to achieve in terms of magic? What was the goal?

It would be transformative in some way that may be more than what they looked like. They would have a presence. I was always looking for transformative shapings by repetition.

And you were influenced by Navajo blankets?

Yeah, Tony Berlant was a big collector and all the artists had to get these Navajo blankets from New Mexico.

And what did you like about them?

I love the thing that was called lazy lines in the blankets. And horizontal lines, they were applied by putting a strip of wood on one side of a stretched canvas and putting nails every quarter of an inch all the way down and taking a plumb bob that was full of graphite; basic colors of graphite. I dumped powdered pigment in the plumb bob container where you pulled the string out and stretched the cloth and you would snap it. And when the snap lines hit the canvas this splattered primary colors to the surface and I would take a spray gun and hit those with water so they would bleed and put tape in diagonals arbitrarily across the surface, 18 inches, 2 or 3 feet long, so when the lines were released on the canvas, that part would be interrupted by the tapes running in diagonal ways similar to lazy lines in the weaving of Navajo blankets. So the process told the visual story and invented formations that I couldn’t have thought of, which was my game of discovering colors and shapes. Then I turned the canvas, pulled it off the panels that it was stretched over, and put it face down.

There’s one listed in the catalog as dated 1971-72 and it has blue and red lines on it.

That’s right, those are the first ones. I put them on a Mylar table that was on the ground that I built with gutters all the way around, like rain gutters. Then put it face down so the backside was up and then poured resin all over that and scraped it all to the edges where the gutters gathered the resin. I did this in the studio I had in Venice on the boardwalk. It had a big outside area.

Other artists were using the resin material at the time?

Yeah. DeWain Valentine and Fred Eversley. They made clear castings with that. I wanted mine more rough. I didn’t want it to have a finished product in that sense.

The so-called Finish Fetish is legendary, and I think John McCracken was known for his perfectionism.

Right he was. And my pal, Jimmy Hayward, used to get the blocks and drive them out to his place.

Yeah, just recently Jimmy was telling me that he was amazed at McCracken’s obsession with getting the surface of the resin perfect.

McCracken had a studio out in New Mexico and it had a little garage with just a hand fan that pulled the fumes out and he’d pour all that stuff over until he developed a method that made them quite beautiful, they were these planks that were 8 feet long and these planks would just lean up against the wall.

But you were more interested in the roughened nature of what would happen with the pours, not smoothness.

Right, the pours and wetting the canvas with resin and it would bleed through to the other side when I pulled it off the Mylar table when it dried. I liked the reverse side since I put it face down and poured the resin on the backside it bled through to the front and made all the snap lines bleed in and adhere to the canvas.

The question is whether they are drawings or paintings or both?

Right, they are both.

And did you plan the rough edges?

This wasn’t something I thought of before, like most of the operations, I find them out in execution of the process.

Through experimentation?

Process is the thing wherein you catch the conscience of the king.

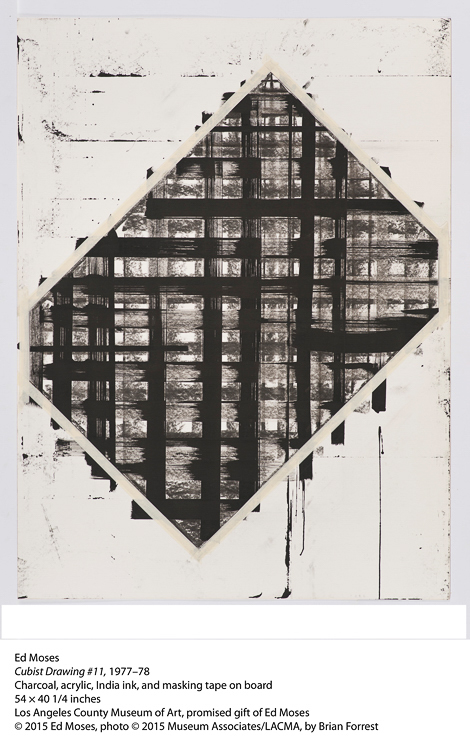

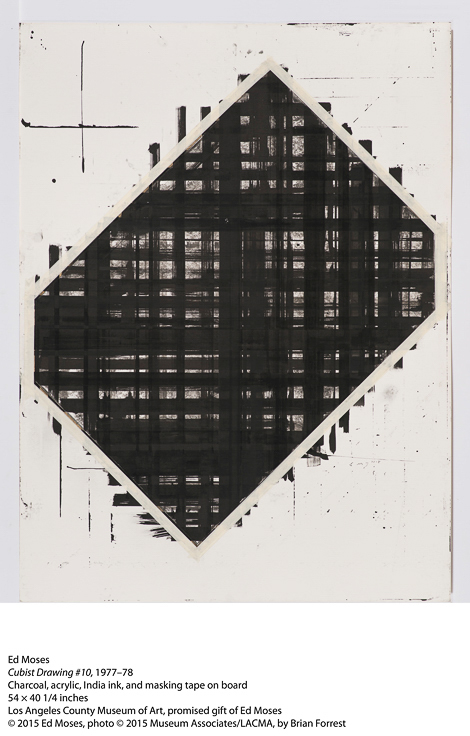

Why did you eventually fix on the image of the grid?

I got interested in the grid from the crisscross action in certain Navajo blankets. And I rotated the grid 45 degrees so it didn’t reinforce the geometry of the plane that they were applied to. I wanted them to float free rather than reinforcing the vertical horizontal of the plane.

The catalog mentions Piet Mondrian who rotated the grid in certain of his works.

Yes, Mondrian was interested in locating the vertical horizontal and reinforcing the geometry of the plane that exists and I wanted to break that and rotate it so it didn’t reinforce the plane.

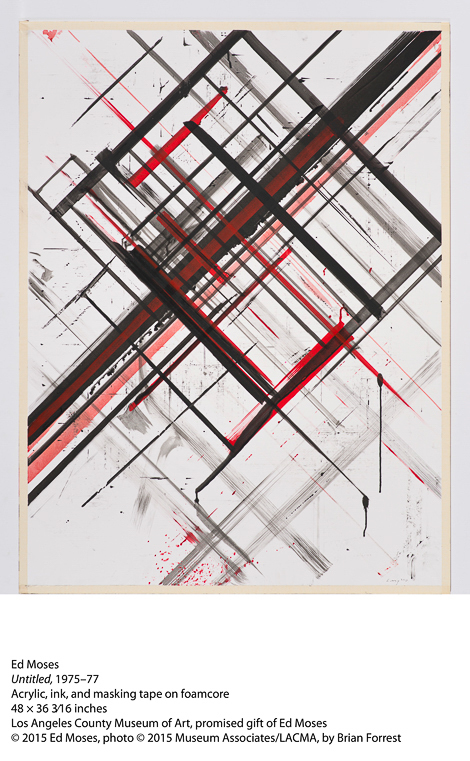

There’s a grid drawing in the catalog, which is from ’75 to ’77, which shows the grid rotated and there seems to be a lot of drips and stray marks.

The paint was very fluid so when I used brushes on a guide on an easel, I had these plastic 45 degree triangles made by Jack Brogan and I slid those along like you would down a t-square, only it was a big board, and I would repeat the diagonals going in both directions, and the paint would be fluid so it would run down and then as I slid the triangle across the face of the runs, they smeared shapes in paint by sliding the triangle.

And when it came to drips, you just let that happen?

They happen naturally and as I slid the big triangles across the surface of the paintings I was making they would destroy the runs and make vertical horizontal, which opposed the 45 degrees of the triangles and smeared them into an overall visual discovery.

Would you say the grid was an obsession?

It became an obsession. I thought if I repeated these things enough times they would escalate into some kind of presence that had something kind of magical.

In other words, transcendent.

It wasn’t just the line— it was a presence that transcended just lines. I’d keep doing them over and over again until they took on this transformative power. In Buddhism it’s action without goal. Performance is the activity without any expectation of discovery so the goal is not the magic. The process is the magic.

And would you say that’s something that you seek to achieve every day that you work?

Every day that I live.

In the mid ’70s, you shifted more toward the canvas and left drawings behind.

I was just lucky I found a way to work on canvas applying resin and snap lines, so it was process without goal. Discovery was activated and the activity was without goal.

You were doing a lot of grid paintings which became an iconic image for you. In fact, you returned to it time after time, including last couple of years.

That’s right. When I lose my way, I go back to the grid. When I lose the activity of paint, I return to the grid and paint or ink are applied with a foam brush going one direction and the other direction. I did a show at LACMA on all red shelves and I did one room with the diagonal red paint crisscrossing until it covered the whole canvas by repeating it over and over again. And I made the shift to what I call abstract, where rather than applying with the brush in diagonal ways, I poured it across the surface. So it would set up uninterrupted, uninflected in applications. And that room, I called the abstract room. And the other room with the diagonals, I called the cubist room. There were three paintings in each room and both rooms glowed red.

And what year was that show at LACMA?

It was 1976 and Stephanie Barron put it together. That was the first show she was given by Maurice Tuchman.

And all these years later, you’re having another LACMA show. What a great run!

I’m very grateful for it.