In September I managed to view the last day of the remarkable “Degenerate Art ” exhibition at cosmetics heir Ronald Lauder’s Neue Galerie in New York City, a museum which regularly displays pre-war German and Austrian art. Subtitled “The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937,” the show was smaller than the groundbreaking exhibit curated by Stephanie Barron at LACMA in 1991. However, research into this topic since that show has uncovered significant new details of this chapter in Nazi lunacy.

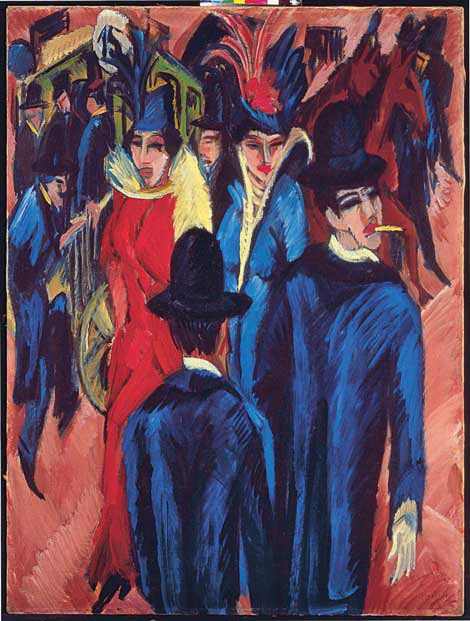

A few years after taking power in Germany, Hitler declared modern art “degenerate” and ordered the confiscation of many modern masterworks from German art museums, art dealers and collectors. The artists so condemned included even Picasso and Van Gogh. But the New York show focused on the German artists, including Beckmann, Kirchner, Grosz, Barlach, Dix, Nolde, and Kokoschka. Masterpieces included Beckmann’s Departure Frankfurt (1932–35) and Kirchner’s Berlin Street Scene (1913). The show was both beautiful to behold and profoundly tragic to contemplate.

The Neue Galerie exhibition also displayed works by artists approved by the Nazis in a show labeled the “The Great German Art Exhibition”: pedestrian art by forgotten German artists depicting perfectly formed nude models, to contrast with the “distorted and diseased” images depicted by the “degenerate artists.” The Nazis put both of these shows on in Munich in 1937. The “Degenerate Art” exhibit drew substantially more viewers and traveled to cities throughout Germany.

The New York show featured some surprises, primarily a physical and digital copy (from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London) of a meticulous inventory of approximately 16,000 confiscated works compiled by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry (hundreds of thousands of additional artworks were confiscated throughout Europe after German occupiers arrived). The Nazis assigned four handpicked “art dealers” to handle the disposition of the art by sale, auction, gift (often to Reichsminister Hermann Goering) and destruction (5,000 works marked with an “X” signifying that fate).

Paging through the digital copy of this fascinating index, I noticed that the most prolific art dealer was listed as Hildebrand Gurlitt, who worked for the Nazis in both Germany and occupied France, and was notorious for seizing the works of Jewish collectors and dealers (he ended up with numerous works stolen from France’s most important pre-war art dealer, Paul Rosenberg). Gurlitt ultimately stashed hundreds of works in Aschbach Castle where they were discovered shortly after the war by the Allied art recovery team known as the Monuments Men (depicted in the recent film of the same name). Gurlitt hoodwinked the Allies by claiming he legitimately owned all of the artwork and got away with most of it. He continued to deal in art until dying in the ’50s in a car crash.

If you recognize the name Gurlitt, it’s no accident—it’s been all over the news. Hildebrand’s son, Cornelius Gurlitt, was arrested in 2013 by German police on a train from Switzerland with thousands in cash which he couldn’t explain to tax authorities. A search of his modest flat in Munich revealed a stash of more than 1,400 pre-war masterworks (including hundreds by the “degenerate artists”) estimated to be worth more than a billion dollars. At 81-years-old, Gurlitt appeared to be a Kafkaesque creature who claimed to have no friends, no occupation, and lived a reclusive life with his precious art. Occasionally he sold a work of art to support himself.

After his stash was seized, Cornelius Gurlitt disingenuously insisted, in an interview with Der Spiegel, that all of the work was inherited from his father who owned clear title. But Gurlitt was a pathological liar. Often overlooked is the fact that he had lived with his father in Aschbach Castle when he was 13, surrounded by stolen artwork. His actions over the decades displayed an absolute consciousness of guilt as to the tainted provenance of his bloodstained cache. What was Gurlitt really up to? His life was devoted to concealing the artwork in an effort to outlast any statute of limitations and so escape claims of heirs for the return of art confiscated by the Nazis.

The German government, which at first concealed the Gurlitt discovery, was shamed into posting copies of the works online and creating a commission to review claims of the Nazi victim’s heirs. So far, few if any artworks have been returned to claimants.

In the past 30 years a line of U.S. and European case law has developed giving the heirs of confiscated artwork more rights to reclaim their art. An international compact known as the Washington Conference Principles has been agreed to by many European nations and provides for modification of legal obstacles such as choice of venue and statutes of limitations to give the heirs broader avenues to justice. However, European governments have moved at a snail’s pace on these claims and museums—including some in the U.S.—have sued to stop any transfer of art.

In May of 2014, Gurlitt died, but not before making a deathbed deal to bequeath all of the artwork to the Kunstmuseum Bern in Switzerland. Ronald Lauder, who is also president of the World Jewish Congress, issued a statement warning that there would be an “avalanche” of litigation if the Bern museum accepted the Gurlitt gift. In November, 2014 the Bern museum agreed to take the artwork after a pact was reached with the German government which pledged to hold onto approximately 250 works for which legitimate claims had been made by original owners or their heirs. The museum stated it would not keep any work for which a genuine claim could be made and would appoint its own panel to investigate. The museum also revealed it was left an additional 238 works Gurlitt had stashed in a vacation villa he owned in Saltzburg, Austria, thus making a mockery of his claims of modesty. There is little doubt that many claims to the art purloined by the father and concealed by his son will wind their way through the courts for years to come.