The 2022–23 term has been a disaster for the US Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Roberts, Jr. disgraced himself by spurning demands from Congress and the public that the Court adopt a code of ethics similar to the one covering all other federal jurists. If such regulation had existed, it may have prevented the dishonorable conduct of Justice Clarence Thomas who was Pro Publica exposed as a bought-and-paid-for tool of a right-wing billionaire.

The court’s conservative supermajority flagrantly ignored the prerequisite of standing to sue in overturning President Biden’s student loan forgiveness program and in permitting a woman’s proposed marriage planning website to state that she would not accept business from same sex couples.

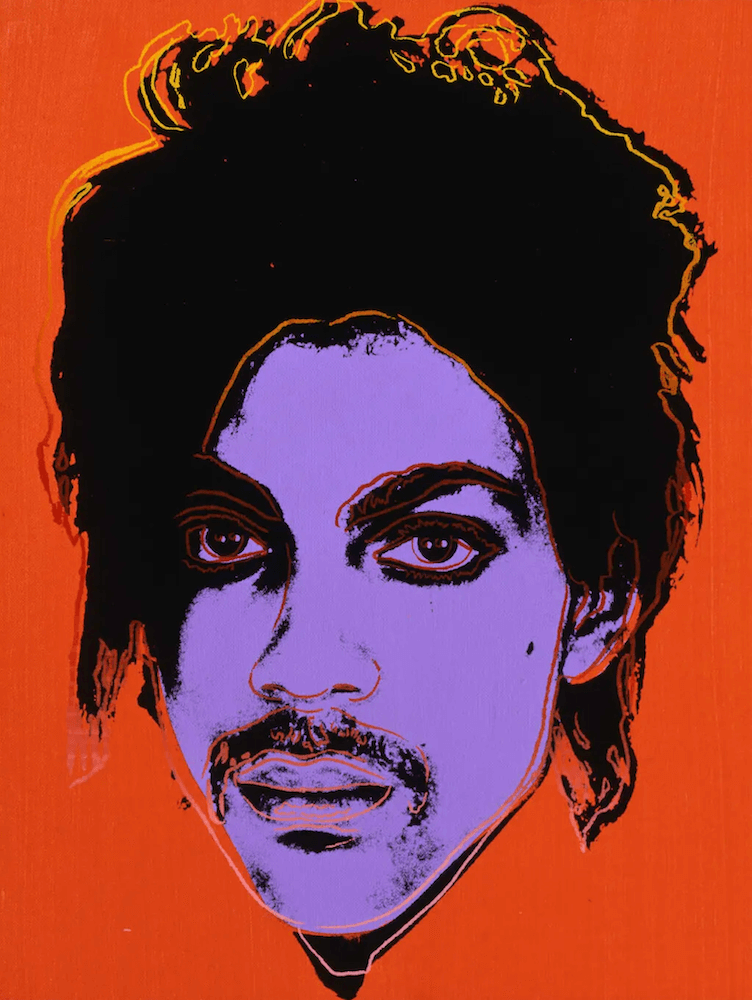

However, amidst all these controversies we should not lose sight of May’s major Supreme Court ruling on the fair use doctrine in copyright infringement cases. As predicted in my column a year earlier, the court upheld the Second Circuit Court’s ruling that the Andy Warhol Foundation infringed the copyright of rock photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince. My forecast was based on the likelihood that, with the departures of Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, the court’s experts on copyright law, SCOTUS would uphold and rely on the Second Circuit’s opinion, especially in view of that New York court’s history of issuing important copyright rulings.

The Second Circuit’s majority opinion was notable in emphatically stating that judges should avoid acting as art critics in determining whether a derivative artwork was sufficiently transformational of another artist’s underlying work of art to qualify for the fair use exception to copyright infringement.

SCOTUS, putting aside ideological lines, ruled 7 to 2 in Goldsmith’s favor, with liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor writing for the majority. The dissent was penned by liberal Justice Elena Kagan and joined by conservative Chief Justice Roberts. The ruling was even more unusual for the overt sniping between Sotomayor and Kagan.

In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed Goldsmith’s photo of Prince for $400 for a single use to illustrate an article titled “Purple Fame.” Vanity Fair hired Warhol to produce his take on the Goldsmith photo and he created 16 silkscreens in a variety of colors—they went with a purple version. On Prince’s death in 2016, a special issue was printed and the Warhol Foundation was paid $10,250 for a license to use the orange image of Prince on its cover. This time Goldsmith received no compensation for the use of her photo.

Goldsmith sued the Foundation in federal court for infringement. In its defense, the Foundation’s lawyers argued that the fair use exception applied. Several elements must be proven for successful fair use determination. The two most important are that 1) the artwork must be “transformative” of the underlying work and 2) an assessment must be made of the of the derivative artwork’s impact on the on the original work’s commercial value in the marketplace.

The SCOTUS majority found that not only was the Warhol work not sufficiently transformative of the photo, but more importantly, that Goldsmith and the Warhol Foundation were competitors in the marketplace. Sotomayor wrote, “Such licenses, for photographs or derivatives of them, are how photographers like Goldsmith make a living. They provide an economic incentive to create original works, which is the goal of copyright.”

Sotomayor also rejected the Foundation’s argument that Warhol sufficiently transformed the Prince photograph by cropping, shading and coloring it.

The upshot of the majority opinion is to deemphasize the transformative element of fair use and focus more on the commercial impact the unlicensed usage had on the original work. The impact in this instance was glaring—Vanity Fair only paid Goldsmith for the earlier use of the Prince photo, and only paid the Foundation for the 2016 issue.

Justice Kagan in her sneering dissent wrote: “All of Warhol’s artistry and social commentary is negated by one thing: Warhol licensed his portrait to a magazine, and Goldsmith sometimes licensed her photos to magazines too. That is the sum and substance of the majority opinion.” Kagan added that the majority opinion reduces the editors of Vanity Fair to choosing between the Goldsmith and Warhol images with a flip of a coin without regard to artistic merit.

By my reading, Kagan’s dissent seems to exalt Warhol as an art god, while brushing aside Goldsmith as a mere mortal, but that is not fair to the myriad of artists who are copyright holders. Indeed, as the Supreme Court majority makes clear, artists are to be treated as equals under the law for purposes of copyright.