Should an artist’s vile personal acts or beliefs be considered in whether to hear or view their work?

The Me Too movement has pushed the private behavior of artists and performers into the public square. Accusations of sexual harassment have damaged the reputations of dozens of artistic figures from Chuck Close to Kevin Spacey. The question is whether these controversies—proven or not—should be cause for a boycott of a performer’s works. Should people turn off Michael Jackson’s music and Woody Allen’s films even though the accusations against them have never been proven? Should an artist’s vile personal acts or beliefs be considered in whether to hear or view their work?

One of the oldest controversies involves the racist writings of the German composer, Richard Wagner, whose Ring cycle is usually an event whenever and wherever it is staged. Wagner was anti-Semitic and was worshipped by Hitler. Some of Wagner’s warped 19th-century writings were referenced in anti-Jewish Nazi propaganda. While I’m an avid fan of the LA Philharmonic, I’ve never attended a Wagner concert. The main reasons are that I do not enjoy Wagner’s music and because I decline to support a racist composer or artist in any way—even by buying a ticket.

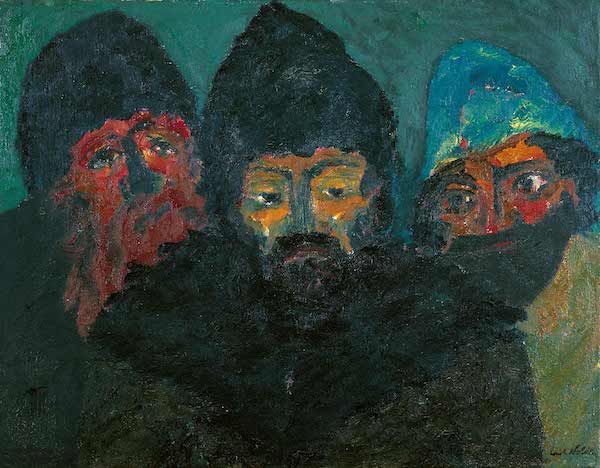

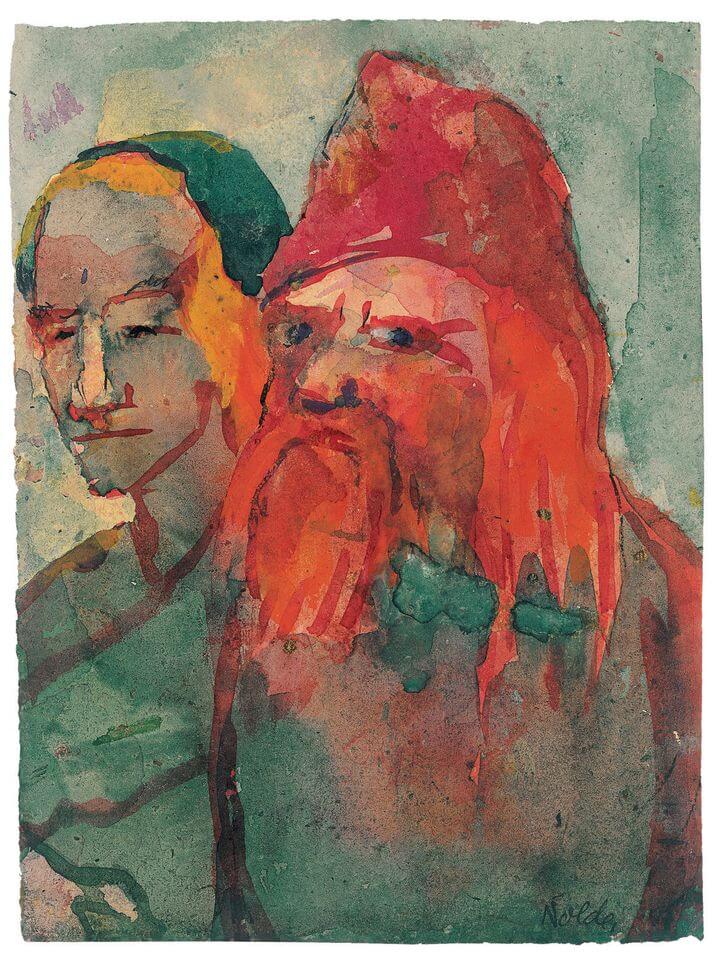

Controversy surrounding German Expressionist Emil Nolde (1867–1956) was recently revived when Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to remove two of his paintings that were hanging in her office in the Chancellery. Merkel lent the paintings to a recent survey of his art—“Emil Nolde. A German Legend: The Artist During the Nazi Regime” currently showing at the Hamburger Bahnhof museum. This provided Merkel with a convenient excuse to announce that the works wouldn’t be returning to her chambers. The chancellor made her decision after the Nolde Foundation’s new leaders decided to open its 25,000 documents to the public. Amongst the trove was renewed evidence of Nolde’s unswerving allegiance to the Nazi party.

Nolde’s affiliation with Nazism was not just something that started when Hitler took power in 1933; he had been an ardent supporter since the early 1920s. To keep in the Nazi’s good graces, Nolde never failed to point out that he had been at odds with what he perceived as the “undue influence” of Jews in European art circles, taking particular aim at artist and writer Max Liebermann, the long-tenured president of the Prussian Academy of Arts until 1933 when he was dismissed by the Nazis.

What makes Nolde’s case so interesting is that despite the fact of his loyalty to the Nazi Party, Nolde himself was one of the greatest victims of the Nazis’ war on what they labeled “degenerate art.” This resulted in the censoring and confiscation of thousands of works of modern art from Germany’s museums and galleries, culminating in the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937 which traveled all over Germany and Austria for the next two years attracting millions of viewers.

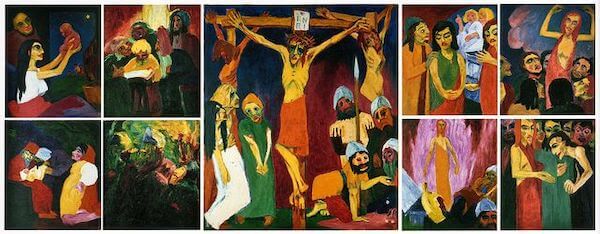

More than 1,000 of Nolde’s works were confiscated during the Nazi lunacy spearheaded by propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (who years earlier, like Merkel, actually hung Nolde’s work in his office). Ironically, the centerpiece of the Degenerate Art exhibit was Nolde’s epic nine-canvas life-of-Christ altarpiece. The problem for Nolde was that his work was firmly rendered in the expressionist style which Hitler (who flunked out of art school) personally despised. No matter how hard Nolde tried to get back into favor with the Nazis, he never would.

After the war, Nolde began a campaign to show that he was, in fact, victimized by the Nazis, but artfully concealed anything that would show his allegiance to their cause. Over time all was forgiven, his work was displayed again, and his reputation whitewashed, until recent years when his own foundation outed him.

The legendary degenerate art show of 1991 at LACMA curated by Stephanie Barron, which gathered many of the works banned in 1937, was groundbreaking. Scholarship into the degenerate art catastrophe was further advanced in 2014 when the Neue Galerie in New York held a show of the work of the “degenerate artists” that included such expressionist greats as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Ernst Kirchner and Nolde. Catalogs from both shows are essential reading for anyone interested in learning more about how attacks on artists and intellectuals are de rigueur for authoritarian regimes (The Nazis also banned music by a long list of composers).

The tale of Emil Nolde has resonance in our turbulent times. If one thing is clear, it’s that an artist’s private misbehavior will always shadow him or her throughout history. There should be no rush to judgment about alleged misconduct of an artist. For some, like Nolde, it took decades for the case to be closed. For others—like Woody Allen or Michael Jackson—evidence is still coming to light.